DISCOVERIES

This section will increase your understanding of research culture and how we as participants can impact changes in this culture. Readers will also learn and appreciate the importance of the different aspects of research.

Culture is hard to define; it is a living, breathing entity that provides the framework for how a group of people should (and should not) act. Here, we will delve into a few key pieces of research culture and provide a general overview.

Research culture encompasses the behaviours, values, expectations, attitudes and norms of our research communities. It influences researchers’ career paths and determines the way that research is conducted and communicated.

The Royal Society, 2020

The Royal Society, based out of the UK, has a great video on what research culture is. To get a strong idea of what we mean when we talk about research culture, check out this video!

The problems outlined in the video are not unique to the UK, and in fact, we see many of the same issues here in Canada. Research in Canada is heavily centred around funding availability, usually in the form of grants and scholarships. By nature of there being more researchers than there are certain funding streams, applications are often competitive between various research groups and even possibly within the same research group. Beyond just getting started however, there are also certain expectations within the research community. This extends to the goal of most academic research in Canada which is the publication of results. With that, there are questions on who gets recognized when, as well as where the research should be published.

There is no denying that there is a competitive side to research. In some cases, it may be a friendly competition between members of the same research group or members of two neighbouring groups working on similar projects. This kind of friendly competition can lead to collaborations or even help to drive creativity and work ethic when it comes to completing projects. In other cases, it may be less friendly (though not necessarily hostile) and this is inherent when it comes to funding applications.

One of the most notable funding pools in Canada is Tri-Agency Funding; that is, grants and scholarships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Social Sciences and Humanities Council (SSHRC), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). There is an inherent competitive nature due to the fact that the number of applicants far outweighs the number of awards granted each year. For example, in 2019, there were 1,693 applications for the NSERC Postgraduate Scholarship-Doctoral (PGS-D) award, and only 394 scholarships of that kind were awarded (NSERC Scholarships and Fellowships Competition Results). So what does this mean?

Each year, students who plan to apply for PGS-D funding or other such high-profile scholarships must ensure their applications are as competitive as possible to have better chances of securing funding, as most Tri-Agency funding is quite competitive. How is this accomplished? Let’s provide an example. The NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s Program award (CGS-M) is awarded to new graduate students each year based on the following criteria: Academic excellence (weighted 50%), research potential (weighted 30%), and personal characteristics and interpersonal skills (weighted 20%) (NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarships-Master’s Program 2019). Students, therefore, must keep in mind what things they can add to their resume or CV. They may end up looking for research opportunities or apply for other scholarships, but these programs are often competitive as well.

Is competition a bad thing? Not necessarily. Competition ensures that the funding being distributed is given out to quality applicants who will lead successful research projects which will aid the scientific community. However, as with any competition, it can lead to animosity between people or it can cause stress in students or faculty who are trying to secure funding.

Part of understanding the culture of research in Canada is realizing the competitive nature of many of these scholarships. Competition is present for undergraduate students, graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and faculty alike. The level of competition and how this manifests culturally varies from institution to institution, but being aware of this facet of the culture is important.

First, a disclaimer: the expectations your supervisor will have for you will vary from person to person and even from university to university. Do you want to know the best way to be sure what the expectations for you are? Ask! Here, we will talk about some general expectations that are common in Canada, as well as some general etiquette that will keep you in good standing with your colleagues.

Expectations

Something you should expect in general is that research is not easy. If it were, everyone would be doing it! Engaging in research is a very rewarding experience as well, but expect that there will be challenging times throughout your project(s). Whether you are an undergraduate student or a graduate student, you will likely be expected to:

- Work Hard: As previously mentioned, research can be difficult. It is important to talk to your supervisor about what hard work looks like to them and to you. Some supervisors will care more about efficiency and may not care about tracking hours in the lab, library, or field. Some supervisors, on the other hand, may want a detailed record of your time. This conversation can help identify what expectations you each have when it comes to scheduling. Does your supervisor want you in the lab 12 hours a day 7 days a week? Do they expect only 3 hours per week? Or do they leave the hours up to you as long as the work gets done? As with all expectations, communication is key!

- Be Ethical: You, and all other researchers, are expected to carry out research in a manner that is ethical. Read up on our page about ethics to learn more.

- Keep Records: Transparency in science, while a part of ethics, is important to note specifically because you may be expected to pass your project to someone else later on. For example, let’s say your supervisor is having you study the long-term effects of a certain pesticide over generations of plant growth and the span of the research project is ten years. As an undergraduate student, you may only work on the project for a year or two, meaning it is incredibly important that when you move on from the research your work is recorded, easy to understand, and highly specific. You will of course still be credited if the work gets published, even if it is ten years down the road, but that doesn’t change the fact that you will have needed to pass your work on to another student, thus ensuring the integrity and continuation of the project.

Etiquette

In Canada, as with many countries in the world, when you work on a research project you will usually be doing so as part of a team. Either you will be taking on an individual piece of a much larger project by yourself, but still contributing to a larger whole, or working on a project side-by-side with some of your other team members. In some cases, however, you may have a small research project that is more of a closed-system in which you carry out the entirety of the project: this could be for a Directed Studies course for credit or for an honours thesis, depending on your institution. Regardless, the overall point here is that you will very likely be working with or around other people. Some general etiquette points to keep in mind are as follows:

- Punctuality: If you have an agreed-upon schedule with others, be sure to stick to it. Some projects may require the whole team to be present before starting, plus it is a good way to show your colleagues that you respect their time.

- Cleanliness: While this is especially true in a lab setting, it is important in most research settings that if you make a mess while in shared spaces you should clean it up. Don’t force others to put away your textbooks for you or put your colleagues in the position of needing to put away your glassware.

- Be Polite: It should go without saying, but an important part of research is being polite to your colleagues. Saying hello and goodbye, please and thank you, and making an effort to get to know your colleagues are all important parts of building a healthy culture in your research community. You don’t have to be best friends with everyone, but you should be polite and considerate of others!

In Canada, the publication of results is one of the most commonly used metrics for success. More specifically, people care about how many papers your name appears on (and in what order) as well as the quality of the journal you publish your results in, keeping in mind that some journals are reputable and some are not. Let’s break this down one thing at a time.

Authorship

In academia, one of the most important things in maintaining integrity is giving credit where credit is due. This means that while you must cite your sources, you must also give credit to all of the people who helped with the project your paper is about. This is what we mean when we refer to authorship: people who are listed on a manuscript as authors. In most cases, this refers to any individual who provided a direct and significant contribution to the project. For people who contributed to the project in a smaller way or a more indirect way, they may be given credit in an Acknowledgements section rather than in the authorship section.

In some fields, this is a streamlined process because authors are listed in a defined order, such as alphabetically by last name. In these cases, little to no emphasis is placed on whose name appears first on the paper. However, in many scientific fields, authorship order is a direct communication of hierarchy in terms of that project. In these cases, the first author is the individual who put in the most work on the project and as such is usually the one who physically writes the manuscript. The second author contributed less, and so on and so forth. However, the author listed last is often the leader of the research group and this placement identifies them as such. It is important to talk to your supervisor and colleagues early on in order to avoid conflicts in authorship claims later – this article from Canadian Science Publishing (2018) provides great insight on how to do just that.

Journal Quality

Researchers should want to publish in journals that are high quality and ones that are reputable. Good-quality scholarly articles have many things in common. For example, they will usually have submitted papers through peer-review, a process in which experts in the same field who are not part of the project in question critique the paper, look for inconsistencies, and provide feedback for the researchers: the process for peer-review should be publicly and easily available (Canadian Association of Research Libraries, 2020). These journals also have avenues to retract papers later deemed to be false or unethical so as to be transparent and fair. But how do you know which ones are reputable?

Impact Factor

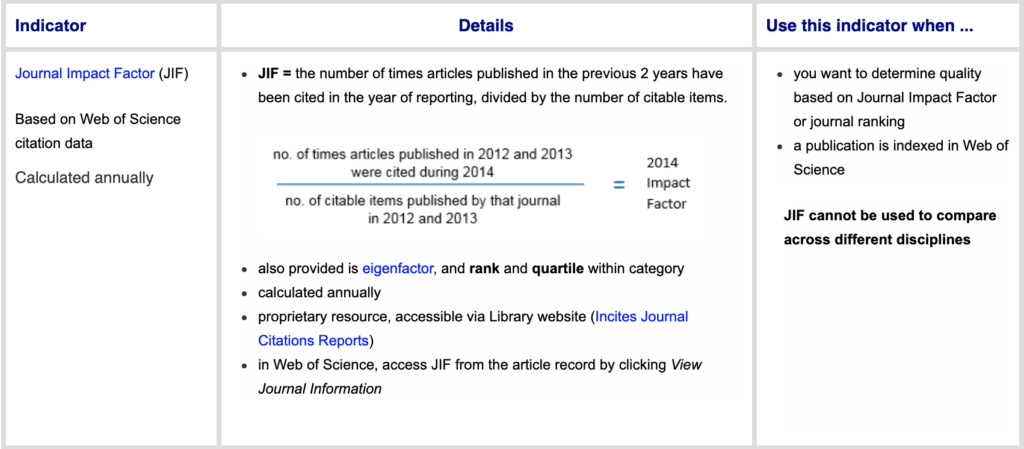

Journal Impact Factor (JIF) is one way to measure the quality of a journal. JIF is a value calculated by taking the number of times articles within the journal were cited and dividing it by the total number of articles that could be cited within that same journal. So for example, if a journal published 50 papers and some number of those papers were cited by other researchers 200 times, the journal would have a JIF of 4.0. Generally speaking, a journal impact factor is a good sign of a reputable journal. However, there are always exceptions, so remember to use a variety of metrics when considering a journal’s credibility.

Monash University. 2019. Research metrics and publishing: Journal Quality and Metrics. Accessed 20 July 2020 from https://guides.lib.monash.edu/research-metrics-publishing/journal-quality

CiteScore

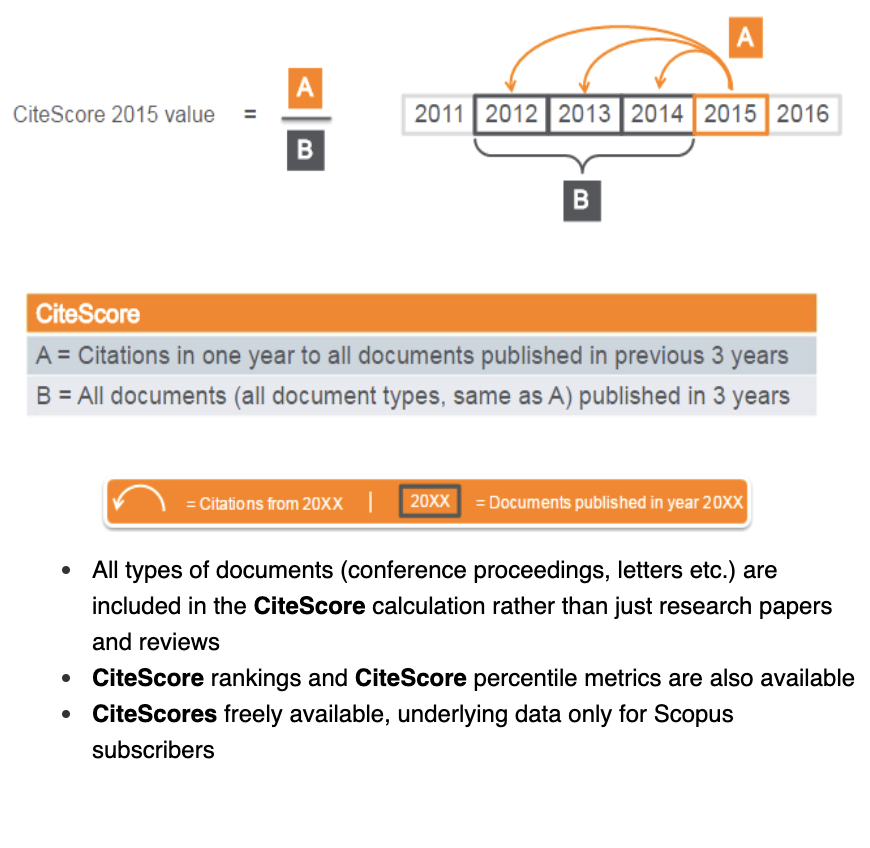

If you want an alternative metric to JIF, you can use CiteScore, which is, “the number of times documents published in the previous 3 years have been cited in the year of reporting, divided by the number of documents.” (Monash University. 2019. Research metrics and publishing: Journal Quality and Metrics. Accessed 20 July 2020 from https://guides.lib.monash.edu/research-metrics-publishing/journal-quality)

Monash University. 2019. Research metrics and publishing: Journal Quality and Metrics. Accessed 20 July 2020 from https://guides.lib.monash.edu/research-metrics-publishing/journal-quality

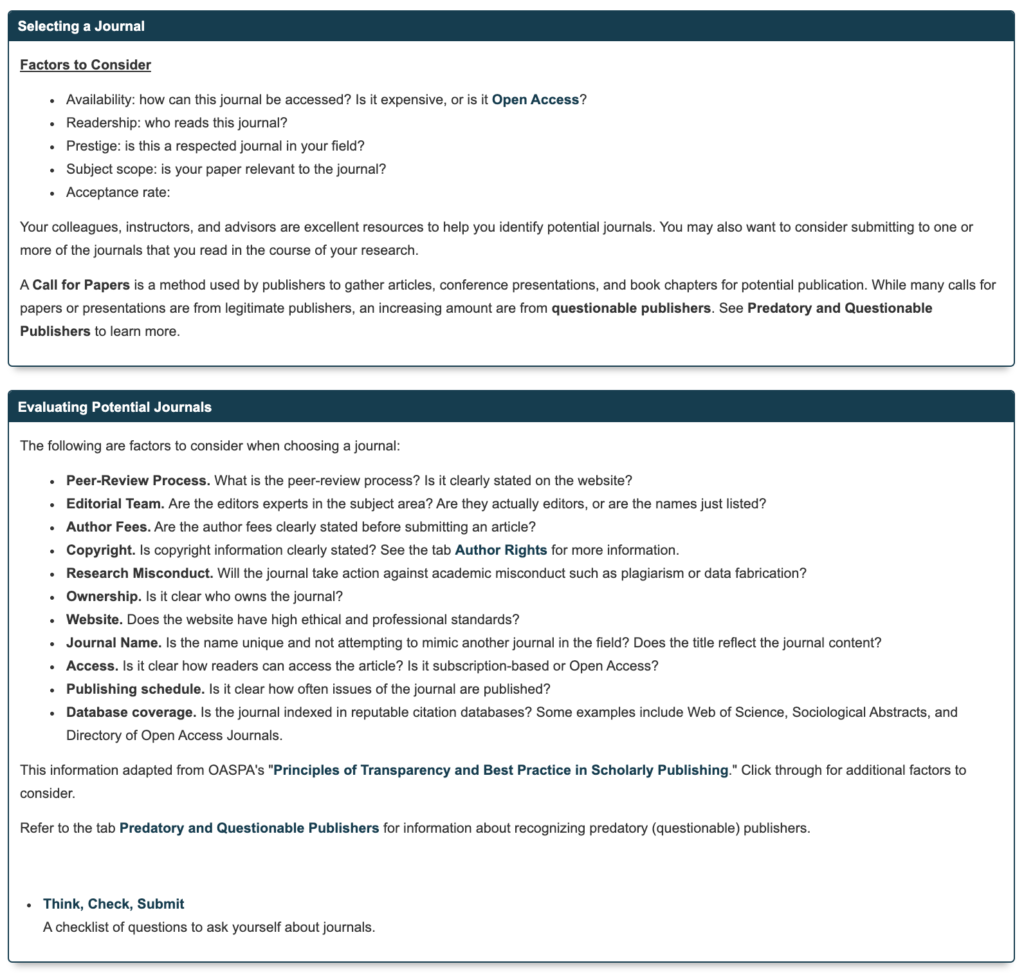

The Thompson Rivers University Library also has some resources on how to spot a good journal for publishing. Their website has the following information which lists some excellent criteria though a more qualitative lens rather than a quantitative one:

Thompson Rivers University. 2020. Publishing your Research. Accessed 11 August 2020. https://libguides.tru.ca/publishingresearch/choosingjournals

Lastly, it is important to simply have conversations. Talk to your supervisor or your colleagues and get a good idea of which journals are reputable and which journals are respected. Some journals may have their credibility ebb and flow over time while others may serve as a benchmark for greatness unhindered by the passage of time. There are a variety of factors to consider; understand that these factors will change over time, so it is important to be constantly aware of the journals that are out there.

TAKEAWAYS

- Improved expectations of the layout of the research.

- Understanding the steps to the publication of papers.